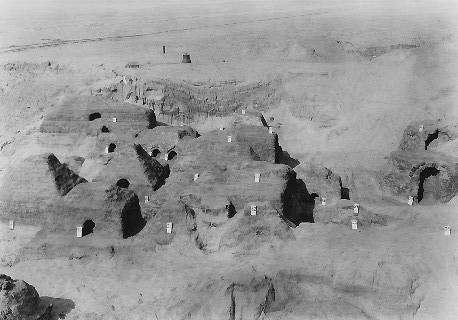

View to the northwest of the excavated tomb field showing pyramid-roofed tombs

Today the stretch of desert plain where the necropolis once existed is bisected by the El Nasseri irrigation canal and lies close to or under the cultivation. In 1935, according to Peterson's description, as preserved for us in his journals and correspondence, the site possessed a rolling terrain punctuated here and there by hillocks -- hence its Arabic name kom.

Originally, the cemetery sloped gently to the South and to the East, and its western perimeter bordered the higher level of the Libyan Desert. Unfortunately, the exact location of Peterson's forty tombs is lost, due to the agencies of the dune-scarping wind and the episodic pillaging of the site by antiqua hunters.

Among the twenty-four types of tombs, two were particularly popular: the barrel- and the pyramid-roofed, that exhibit some fourteen variants. Decidedly very numerous were the "slipper tombs," essentially field stone, mudbrick and clay-formed enclosures for individual, in-ground burials.

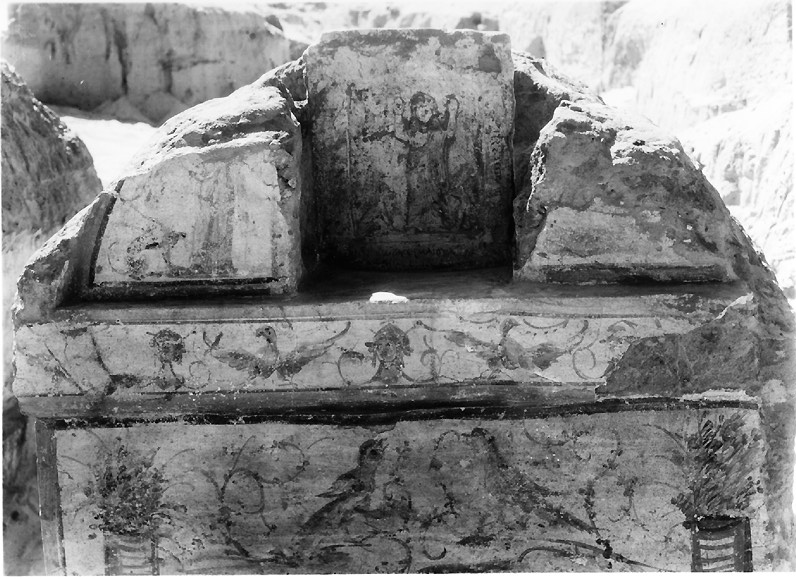

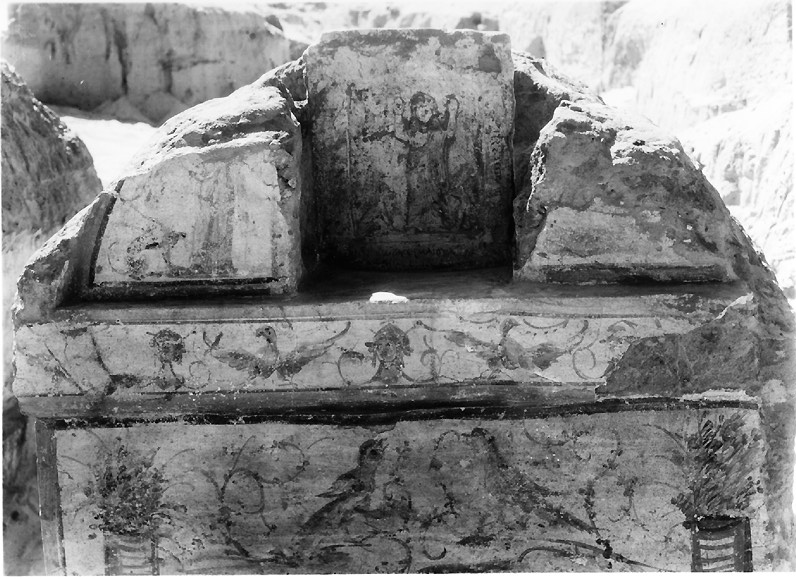

In contrast to the in-ground "slipper tombs," the roofed tomb structures were placed on mudbrick podiums. Attached to their eastern facades were projecting altar tables or simple platforms. The surfaces of the mudbrick tombs and their attached altars were stuccoed and became fields for fresco paintings of festive "peopled" garlands, accoutrements and personnel of the cult and linear framing bands. It seems that the fresco decorations were intended to convey the impression that a perpetual festival for the dead was in progress in front of and presumably beyond the tomb structure's symbolic entrance.

Archival photographs of Peterson's well-documented excavation reveal that the tomb facades generally faced eastwards towards the rising sun, an arrangement that is traced back to Pharaonic times. The tomb's mudbrick podiums were built into the rolling terrain in conformity with the topography. This random pattern of building resulted in winding alleys -- possibly a dim reflection of the now alluvium-buried townscape of Terenouthis.

Apparently the size of the tomb and its degree of decoration were determined in part by the owner's wealth. Similarly, a tombs position relative to the center of the cemetery correlated with the owner's resources as the larger and more lavishly decorated tombs are located there. It is ironic that lesser tombs on the periphery of the cemetery survived as a rule relatively well, as they tended to be covered earlier and their presence was less apparent next to the desert's discontinuous edges. The larger tombs in the central area of the necropolis, on the other hand, were more easily detected by the grave robbers.

In regard to the interment practices of the Graeco-Roman period it is to be noted that no burial discovered either by Peterson or the Egyptian excavators was actually situated either within or directly beneath a podium tomb's structure. Rather, the corpse was placed in prone position with the arms naturally at rest across the lower body, and at varying depths and angles around the tomb's podium. Occasionally, the individual's personal funerary stele is placed against the podium's base, just above the deceased's head. It is concluded from the available evidence that most if not all the early imperial tombs at Kom Abou Billou were cenotaphs, i.e. "empty tombs," dedicated to a particular family, or possibly a clan.

In later centuries the narrow alleys among all the tombs became sand-engulphed and forgotten. By or just before the fourth century AD the pattern of inhumation changed, becoming more random and in the nature of simple depositions wherever there was space and depth. In the accumulated layers of debris and sand later burials in their hundreds took place. Some were merely covered by sand; some were encased with a bodycast of plaster. This burial pattern of Late Antiquity left a chaotic stratigraphy, hopelessly complicated by the mining operations of the tomb robbers.

Pagan burials cease after the Islamic Conquest and no ritual Christian burials have turned up.

The festive fresco paintings and the offering altar tables of the tombs were complemented by formally carved and painted funerary stones. Recessed in niches either in the tomb wall or the vertical screen wall (tympanum) of the gabled roof, they align at eye level with the tomb facade's central axis.

Barrel-vaulted tomb with its stele In situ, which belonged to a fourteen-year-old girl, "Isidora, the daughter of Hermaios." Dated by the stele to the 2nd quarter of the 2nd century AD.

* * *

Also, the funerary stele and its images were undoubtedly intended to focus the viewer's attention, for it was in front of and to the stele and its images of the departed that the rituals of the ancestor cult were performed, including sacrificing, cooking, feasting, music making, chanting and possibly dancing (deduced from the discovery of several finger cymbals or zills among the tombs).

The existence of such an elaborate funerary cult at this site is almost predictable, since ancestor worship is attested in Egypt from as early as the third millenium BC. Since prehistoric times the tribes inhabiting the Nile Valley believed that the dead required physical sustenance for their afterlife activities. In practical terms the spirit-food was provided by the deceased's family. The inducement to the living was threefold: to lessen the individual and collective grief; to propitiate, i.e. "to satisfy," the ancestor's imagined needs; to invoke helpful intervention of the satisfied loved-one from the "land of the dead." Over generations there evolved a family-based popular cult of the immortal ancestor involving complex networks of mutual -- even third-party -- arrangements for the provisioning of food and the carrying out of specified rites, especially on the festival days of the Egyptian and later the Greek and Roman calendars.

Essential to the functioning of the ancient cult of the venerated immortal ancestor was the traditional tomb stele, found in many hundreds of Kom Abou Billou. The stelae, as a rule, are framed by some form of architectural structure, the forms and components of which can be directly traced back to the traditional Egyptian temple's columnar entrances. Often found within the columnar porches is an arching, black, ribbon-like motif, centered directly over the head of the figure within the entrance.

There were two popular compositional types found at the necropolis of Terenouthis: (1) the orans or praying figure standing with upraised arms and usually enframed within a portal, and (2) a banqueter or banqueters reclining on a Greek dining couch ( kline). Like the orans, the feasting compositions are similarly framed by a variety of columnar portals. A notable variation of the orans composition is the placement of the figure in a boat. Since the religious rites performed in front of the tomb involved the preparation and presentation of food stuffs to the ancestor's spirit, these stelae, with images of the deceased framed by a portal to the Underworld, were entirely appropriate. Here was a meeting place, a zone of transition, between the upper and lower worlds, where the living and dead might commune.

Traditional superstitions concerning the potential malevolence of the dead dictated that he or she be approached cautiously, i.e. ritually and at a neutral spot, readily identifiable as such. There, the descendants might draw near but at the same time be magically separated from them, for in Pharaonic as in Graeco-Roman times the dead were thought to fear and respect the living as much as the living respected and feared the dead. The tomb's threshold, guarded by the "Lord of the necropolis" Anubis, contained the summoned spirit in a defined place. In this way the threshold of the tomb's porch was a neutral meeting ground within which the dead were consigned to the spirit world while at the same time the living might respectfully approach.